Bill "The Book" Richardson

We have added a new interview "Book" Revisited

Before we begin this interview, let me start off by thanking Ali for the effort that he has put into developing this site, and for posting interviews such as this one. Although I don’t know Ali on a personal level, we have been in contact with each other several times over the years, and he has always been a gentleman. Ali also has my respect because he has had some very good success with very few pigeons, and in my mind that is what the sport should be about.

Q1 Please introduce yourself and tell us how you got started in the sport? Did you have a specific mentor?

Bill "The Book" Richardson Bill "The Book" Richardson

Let me begin this interview by saying that my name is Bill "The Book" Richardson, but everyone just calls me Book (If they like me, and even worse if they don’t). I grew up racing in the 200 member Mountain Concourses with an average shipping of between 1,500 to 2,000 pigeons a week. I obtained my first racing pigeons in 1970, at the age of 11; however, because of an outbreak of New Castle in the California area, I actually didn’t fly my first race until 1973, when I was 14 years of age. Being rather young, those three years of waiting to race were very difficult for me, and I doubt many kids would have hung in there the way I did, especially when you consider that I had never flown a race and really didn’t know what it was all about!

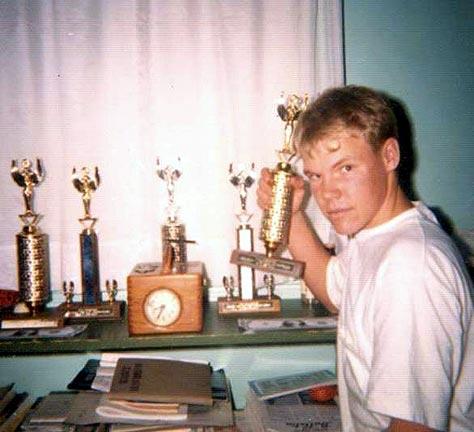

I was very fortunate in those early days to have a mentor by the name of Don Falkenborg. Although Don wasn’t a big name in the sport, he did have a reputation as an excellent selector of pigeons, and when he had the time, he was also an excellent competitor, but most of all he was a wonderful teacher. Let me point it out before others point it out for me, I wasn’t an easy student to teach because I obviously already knew everything there was to know (or so I thought). This was further compounded by the fact that my pigeons had some excellent success very early on. For instance, before I was old enough to drive, I helped my pigeons win two combine short average speeds, two points championships, three combine overalls, and many top ten finishes including a stretch where my pigeons finished 6, 4, 9, 2, 1, 12, 9, 3 and 1 in the combine in two seasons of young bird short average speed racing.

Early Success Early Success

Part of the reason that Don was such a good teacher was that as a former highly successful salesman, he understood people better than anyone that I have ever met. This ability eventually helped him found a multi-million dollar business, and, as Don’s business grew, his time for the pigeons became far more limited. Consequently, instead of racing pigeons, he chose to study them. However, in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s, fanciers that owned pigeons, but didn’t race, were more frowned upon than they possibly are today, so Don often didn’t get the credit that he deserved.

Because Don wasn’t hurting for money, and because he loved studying pigeons, he put the two together and twice hired Piet De Weed to come grade his pigeons and teach him grading techniques. Piet was not known for giving away information freely, but because of Don’s ability with people, he was able to quickly win over the less than forthcoming Piet. Luckily, Don was willing to share this information more freely with me.

Life can be funny, and, at least for me, many of my greatest moments in this sport have happened by coincidence. One of those coincidences happened in 1981, while I was attended College at the University of Arizona. It happened that I went the Department of Animal Sciences looking to use a dissecting scope, and, instead, with the help of the renowned biologist and author, Dr. Robert B. Chiasson, I eventually came away with the concept of eye mechanics.

While this all sounds very scholarly, the truth is that one of Dr. Chiasson’s assistants had a grant to study thermal displacement in the pigeon eye, and they needed some pigeons for their experiment. I agreed to supply the pigeons, and they begrudgingly agreed to let me hang around during the experiment, which lasted approximately a year. During that time, I had full access to a great deal of equipment, related reading material, and the knowledge of these two gentlemen. You would be surprised how many questions I can ask in a year! I know they were!

After graduation, my wife and I settled in Tucson, Arizona, where I successfully raced pigeons until 1993, winning an All American Award, President’s Cup and AU Hall of Fame. When I returned to the sport in 1998, I had many more time constraints in my life, so I had to narrow my focus to the breeding side of the sport. Although I will race again, it won’t be until after I retire. While my breeding program takes up a great deal of my free time, I have also filled in around the edges by writing articles, lecturing, and grading pigeons. The advantage in these pursuits is that when I don’t have time for them, I simply don’t do them.

It was the eyesign enthusiast, Myron Kulik, who first suggested that I start writing articles, and he initially put me in touch with Steven van Breemen of Winning Magazine. Since then, I have gained international recognition for my 75 plus articles that are currently being printed in Winning Magazine (English and Dutch), the Australian Racing Pigeon Journal ( English), and occasionally on the Danish site Dansk Brevduesport (Danish), and, after these articles are published, I make them available to everyone at my Hofkens International site at http://www.ehofkens.com/.

From left to right – Eddy Noel, Assistant Editor, Winning Magazine; myself; Steven van Breemen, Editor Winning Magazine (all operating on 5 hours sleep during a particularly busy portion of the lecturing and grading tour in Holland and Belgium)

Since 1987, I have also presented seminars at the San Diego Clubhouse, San Deigo, CA; the Desert Classic, Phoenix, Arizona; twice at the FVC Snowbird race in Los Angeles, California; the IF Convention in Long Island, New York; and the Gopher State Auction in Minnesota. I am also currently scheduled to speak at the Texas Convention in Louisiana in July of 2007.

Seminar - Gopher State Auction in Minnesota

In 2005, through the sponsorship of a Danish Auction, Meldgaard Feeds of Denmark and Winning Magazine, I was invited to become the first American to present seminars and grade sessions in Denmark, Holland and Belgium. This included sessions in Ringsted, Aalborg, and Esbjerg, Denmark; Etten-Leur, and Putten, Holland; and Aalst Belgium.

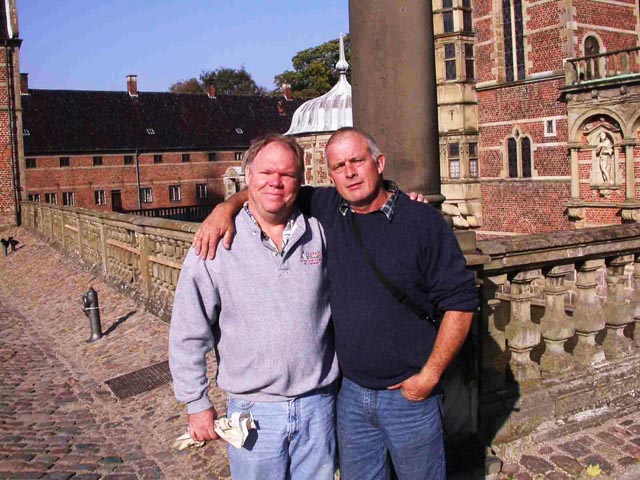

My good Danish friend and student, Steen Haagh, who made the European trip possible

The man that made Steen and I laugh all the way across Denmark - My Danish bodyguard/driver and friend Flemming Christensen

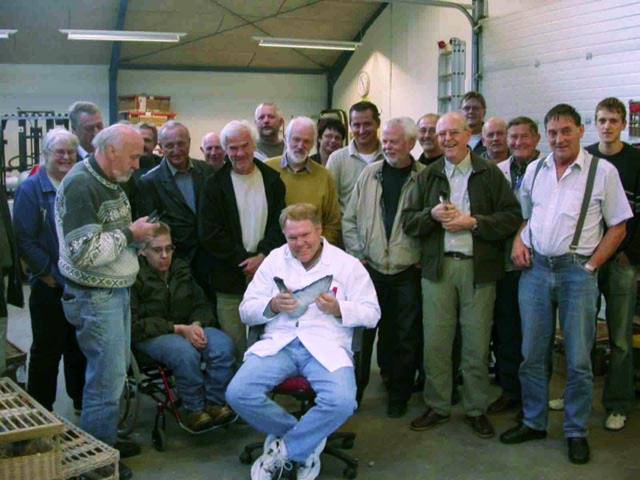

Seminar – Aalborg, Denmark

Seminar Etten-Leur, Holland

Because of personal health considerations, I don’t grade pigeons that often anymore, but on that trip, I professionally graded approximately 3,000 pigeons. A second series of seminars are currently being planned for Denmark in the fall of 2007.

Grading Session –Esbjerg, Denmark

Q2 Amongst the results that you have achieved over the years what are the real highlights?

Three accomplishments come to mind are the back-to-back short average speeds and point championships that I won in Mountain Concourse in my early teens, the great accomplishments of my AU Hall of Fame winner, "Prime Time" who was equal 1st - 125 ml, 1st 400 ml, 1st 500 ml, 1st 600 ml, all in the same season, and finally winning the President's Cup, as a result of my 14 wins in 16 races.

Q3 What organizations do you race with?

As I have not raced pigeons since 1993, there hasn’t been much a reason to belong to any of the local clubs here in Tucson. However, I have been a member of the AU since I returned to the sport in 1998.

Q4 Is there anything more in the sport that you would like to achieve?

Right now, in my current areas of interests, it is hard to imagine that I could accomplish a great deal more in this sport. However, if you had said to me two years ago that I would be lecturing in Europe, I would have laughed, so I guess there is always the potential for new possibilities to come along. My guess is that I will continue doing more of the same by writing articles, lecturing and grading.

Q5 Do you use any preventative medication?

To be totally honest, I have come to hate the word "medication", as I believe that it is the most overused word in the sport besides the word "I" (As in I did this or I did that). Pigeons are naturally a very hardy species. If you go the park and watch the wild pigeons, as I often do, you will see that there are a number of sick pigeons, as well as a number of pretty healthy ones. Here they are all mixed together and yet many remain healthy. Why? Because, as I said earlier, they are a hardy species, that has built up an excellent immune system through a "survival of the fittest" approach.

My first grading session, 1960.

The more we medicate, the more we strengthen the weak and weaken the strong. In a sense, through medication, we are rewarding weakness and penalizing strength. Instead, it is my view that we need to eliminate the weak and work with the strong. Medication is generally a knee-jerk reaction to two much bigger problems in this sport, increasing shipping limits and overcrowding. When I was a kid, most lofts had a total of 125 pigeons, and the shipping limits were 10 and 15 pigeons in most areas of the country. Today, in an effort to compete under the much larger shipping limits, many fanciers are shipping 30, 40 or 50 pigeons, and, as a result, they are now keeping 300 pigeons in the same lofts that used to hold 125 pigeons.

I am not saying that we can necessarily do without medication, but at the same time many fanciers are either using too much medication, concentrated medication, combined medications, the wrong medication, or medicating for an improper duration. Again, in doing so, these fanciers are helping the weak at the expense of the strong, and, as a result they are destroying the natural immunity of a naturally hardy species.

Q6 When you raced, did you give any special treatments when the pigeons return from the race as a precaution against anything that they may have picked up in the basket?

Many fancier spend their time complaining about how sick their pigeons get on the truck. My good friend Marty Ladin always says, "Good pigeons don’t get sick," and, while this is something of an oversimplification, they do tend to get sick far less easily. Consequently, while there may be sickness on the truck, if it isn’t the strong pigeons bringing the sickness home, it must be the weak pigeons. Therefore, if it takes a weak pigeon to bring the sickness to the truck, and a weak pigeon to bring it home to other lofts, then it seems to me that the real problem here is that too many fanciers are working with weak pigeons that should have been eliminated long before they ever got on the truck in the first place. Assuming this to be the case, eliminating weak pigeons before the fact would seem more prudent than medicating after the fact.

Q7 When you raced, were there any special treatments that you gave your birds once the season has finished? What do you recommend the readers to do with the birds?

Again, assuming that you haven’t attempted to baby the weak ones along through medication, by the end of the season, the weak ones should already be gone. Therefore, you should be working with fewer and stronger pigeons. These pigeons do not need medication, and generally they will recover with a healthy portion of barley added to the feed, and where possible a little free-lofting.

However, if the fancier has helped his weak ones hang in there, then once again, he will be forced to medicate at the expense of the strong, and the entire cycle will begin again the next year.

Q8 Do you attach any importance to grits and minerals or can the pigeons get what they want when they are out of the loft picking on the ground?

My pigeons always have good clean European washed grit and minerals in front of them, and they usually eat a lot of these items when they are breeding, but very little otherwise. I believe that the race team can pick up a lot of what they need off the ground, however, allowing them to do so greatly depends on the environment around the loft. Here in Arizona, it gets very hot, so worms are not much of an issue, and because the dirt is sun-baked it is usually very sterile. Generally, I free-loft my race birds once a week, during the races, and I always free-loft the old birds while they are mated before the races. While free-lofting can cause some problems, it is a great way to reduce stress, and it can be of great benefit to the immune system.

Q9 What do you feed? Do you measure the amount that you give to each pigeon? Are they fed individually or as a group? Do you feed light to heavy or alter the diet in other ways throughout the week? Do you change the diet with the seasons?

My feeding systems are very much based on whether I am feeding once a day or twice a day. If I am feeding once a day, I always feed in the morning, and I generally leave the food in front of them for an hour. Under this method, I just use a regular mix, and they can choose what the want to eat. My pigeons work hard around the loft, and while they are hungry after their workout, they know that the feed will be there, so they never pack it down. If I didn’t have to go to work, I would probably leave the food in the loft until noon.

While feeding once a day is the easiest way to race, when I am really trying to win, I feed twice a day. This method is about 10 times more complicated because I store all the grains separately, and I mix according to the day and what I feel they need. Under this method, they are hand-fed on the floor, and it is critical that the fancier know when to shut the food off. This system only works well when you live in an area where the races go off as scheduled. There are some areas in the United States where the weather changes so quickly that many clubs wait until the weekend to determine which day race will be flown, and twice a day feeding will do nothing but get the fancier in trouble in those areas.

During the season, I use some combinations of red winter wheat, milo, Austrian peas, popcorn, safflower, barley and sunflower seeds. I also use small amounts of flax, red and white millet, and hemp. However, again, everything depends on the day and/or the need.

Q10 Do you use any floor dressing or do you scrape the floor clean?

In my view, during the races, the loft should either be cleaned twice a day, or not at all. For my own personal heath, I prefer to clean the loft out twice a day. During my racing days, I housed a team of 60 young birds in five – 6’X 8’ sections. Therefore, even when I kept the pigeons in for the day, I could move them from one section to another while I was cleaning the loft. With so few pigeons, I could clean the loft in about 15 minutes.

Part of the reason that I like to scrape the loft twice a day is so that I can examine the droppings on each perch. With so few pigeons, I have a pretty good idea who is sitting on what perch, and because I release my pigeons to fly around the loft at 15 minutes before sunrise, they usually don’t have time to trample their droppings on the perches.

Based on the color, consistency, shape and dampness of the droppings, I make the decision on how I am going to mix the food for that day. I actually grade the droppings before I begin cleaning. In my view, what comes out tells me what should go in, and what goes in tells me what should come out.

Q11 Do you use any form of heating system in any of your lofts? Do you think it would be advantageous for the birds?

In areas where the floor tends to get damp over night, it is probably a good idea to heat the floors, but I don’t really think that it is a good idea to heat the loft to keep the pigeons warm. While it is true that pigeons do come into form easier that way, as the temperature goes up the moisture in the air goes down, and this can easily lead to respiratory problems. If you are going to warm the floors, pig warming blankets seem to work pretty well.

Racing Methods

I haven’t raced pigeons since 1993, and, because of this, there will be those that discount what I have to say about racing, and that is fine. However, let me just say that while I don’t have the time to race anymore, I still work very closely with several top fanciers around the world. As I have worked with Steve Zammit of Australia the longest, I thought it might be best that you hear from him instead of me. Steve and I have been in very close contact for approximately 7 years now, and during that period, we have written close to 5,000 emails to each other. Steve is my most accomplished student, and knows my selecting, breeding and racing methods better than anyone else on the planet. Therefore, I have asked Steve to prepare a couple of paragraphs on my behalf.

One of the top fanciers in all of Australia - Steve Zammit

My name is Steve Zammit, and I race pigeons in Sydney, Australia, in the Central Cumberland Federation, which had 455 competitors this season and ships approximately 8000 birds per race. I fly in partnership with my father in the Smithfield club under the name of V & S Zammit. We have always flown a combined yearling and old bird schedule, which is generally about 23 weeks long, and normally starts the 1st Saturday in May and finishes 23 weeks later. Our races start at approximately 120km and steadily progress in distance to 1000km. Each year, our Federation switches the direction of the race course so as to make it fair to everyone.

Although we have had many successful seasons as of late, 2006 was an especially successful season for us. Here in Australia, no course is easy, but, this year, we flew the north coast route, which, given its headwinds, is the hardest course of all. This season was further complicated by the unusual amount of rain that we experienced during many of the races. From this route, while I am the shortest marker in the club, and almost in the middle of the Federation. We have an 18 pigeon shipping limit, and fanciers are only allowed to take one prize per race. This year, of the 23 races, two were called off due to bad weather, and I was unable to race two other races due to work commitments.

In a 14 member club, I had the very good fortune to win 8 races and finish second 6 times, while winning the short, long and overall point championships. I also ran 9th in the Federation point score, which given that I didn’t fly two of the races, is quite an accomplishment, especially since seven of the eight that finished in front of me live in the more favorable South East corner of our Federation.

Some of my favorite moments in the season include, having 13 birds on the drop to win one of the races, winning both 400 mile races for the second year running, winning a very tough second 400 mile race by shipping five and clocking the only two day birds in the club, sending 4 birds to the two-day 600 mile race and clocking two on the drop (6:13 a.m.) ten hours out front of my club, and placing 1st Section, 4th overall Federation and 1st Federation in the two bird average.

While I am very proud of all of these accomplishments, I owe much of this success to a fancier by the name of Bill "The Book" Richardson. Over the last seven years, Bill and I have exchanged many thousands of emails in which he outlined his racing, selecting, and breeding techniques. Through this knowledge, I have been able to greatly improve my racing consistency, dramatically reduce my losses, and dramatically improve the quality of my breeding stock.

Because our seasons are so long, most fanciers maintain teams of between 200 and 500 pigeons. However, through Bill’s training techniques, I now have little difficulty consistently competing with teams of 60 pigeons. With such a small team, it is critical that the pigeons recover rapidly after each race, and, through Bill’s methods, I am now able to rest and repeat pigeons far more quickly than ever before. This is primarily because Bill’s system is built around rest, feeding, and loft management.

As an example, several years ago, my entire team was made up of yearlings. Through Bill’s methods, I able to send one cock for 17 straight weeks until it was inadvertently killed in a shipping accident. Another pigeon went 19 straight weeks and even won on the last week it was shipped. These pigeons weren’t just "going" each week, they were placing very high in the club and Federation.

Over the years, I have had the opportunity to meet many great fanciers from all over the world, and, in my opinion, Bill is second to none. In fact, although he has become very popular for his articles, were he based in Europe, he would already be a legend in our sport.

Q12 How do you race your pigeons (what system) and how many? Have you personalized your system or follow a pretty standard method?

While I have flown both widowhood cocks and widowhood hens, I prefer the hens. Overall, the hens are a lot less work, and they tend to be more like young birds in their conditioning cycles. Hens are also more forgiving when the fancier makes a mistake. Should the pigeons need to be re-mated for some reason, widowhood hens are also always 20 days away from a prime nest condition (I have never had to do this, but it is a good theory anyway). Hens can be more easily road trained during the season, and they are usually more successful than the cocks in races beyond 400 miles.

I always say that pigeons will let you do as much for them as you are willing to do. Therefore, I try to keep things simple and keep them doing most of the work. I generally have about 35 hens on my race team and I maintain another 20 cocks that I keep as mates. The extra 15 hens are my yearlings, and to keep the work at a minimum and to avoid the confusion that yearlings can cause, I don’t bother to mate them during their yearling year. If I happen lose an older hen along the way, then one of the yearlings hens can hook up with that available mate if it wants too. I never raise babies from my race team because it is just too much work! Instead, they sit on two sets of eggs for about 10 days. Once the pairs are broken up, the hens only see the cocks for about 15 minutes on the night of basketing, and for about one hour after each race up to 300 miles. After 300 miles the hen gets to spend the rest of the day with the cocks.

Hens tend to do better when they are flown and fed once a day and in the morning. They are generally pretty good about flying around the loft, and mine usually fly an hour and a half to two hours with no real problem. Many fanciers get too proud of how long their pigeons stay in the air around the loft, but it is the quality of the workout that is important.

Unfortunately, hens are not always the greatest trappers in the world, and it is not uncommon for them to sit out for a while after the morning training, and they can sometimes also be difficult during the early races. I guess that you have to take the good with the bad. Probably these days they would do better in this regard because of the electronic clocking.

Hens tend to store fat much more easily than the cocks, so it is important to watch how the weight goes on at the end of the week. Because hens store fat so easily, they sometimes have trouble on the first hot race of the season. During such a transition, it is very easy to lose them; however, after that first transitional week, they handle the heat very well.

Q13 Apart from medication, do the pigeons need any special treatment on their return from a race?

Rest is the single most important element to recovery. It is very important that they get light easily digestible grains upon their return from a race. I never fly my pigeons the day before or after a race for any reason, and, then depending on the race they have just flown, they may not get out of the loft again until Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday.

Q14 If your race team went off form during the season what action would you take to restore their condition?

I would feed them as much pure malt barley as they were willing to eat for four days, and I would keep them in the loft during that time. Usually, going off form is caused by a build up of lactic acid in their system, and the barley will help to purify their blood.

Q15 What is the farthest distance that you would train your old birds or young birds?

My first toss in young birds and old birds is from 30 miles. The second toss is from 50 miles, and the third is from 65 miles. While I do occasionally go to the 90 miles station for a toss, 98% of all of my tosses are from 65 miles. However, when I was stationed in Germany in the late 1970’s, I flew partners with a fancier that trained his pigeons on a bicycle to 5 miles, and then he sent them to a race of about 75 miles, and he did just fine.

Q16 What families of pigeons do you keep?

On my return to the sport in 1998, my partners (today it is only one partner), and I purchased an excellent set of approximately 40 Hofkens; however these pigeons were very line bred and were in need of a cross. Therefore, in 2005, I worked out a deal with my good friend and excellent fancier, Ed Lorenz, to purchase many of his top Horemans. During the 1970’s Ed was known for his Stassarts family and his brother Pete was known for the Horemans. In the mid 1970’s, Ed asked his brother, Pete, for couple of Horemans to put on the race team. As Ed said, "When you send 29 Stassarts and one Horemans, and that one Horemans is your first pigeon every week, there is little point in keeping the Stassarts."

The great United States Champion – Ed Lorenz

From the start, the Horemans were more my type of pigeon, especially since they are very much a hen based family. Prior to my purchasing the Horemans, I had visited Ed’s loft on a number of occasions, and, on one trip, he showed me three inbred brothers that I immediately fell in love with. In fact, I told my life long friend, Ed Shimkowski, "If I had those three pigeons, I would get rid of mine." Well, I don’t have all three, but I do have the best of the three, and when mated to his sister (or anything else), he produces like no other pigeon that I have ever owned! Next year, I will be breeding out of 16 of his children.

Like anything else, there is always a down side to any story, and, in this story, the down side occurred when I handled the three brothers. The truth be told, I was going to have one of those cocks if I had to sell or trade my whole loft of Hofkens to get it, and with this mindset, I was going to need more than one Horemans to support this great pigeon. In truth, in the back of my mind, I never thought the Hofkens were going to be that compatible with the Horemans, but at that moment that wasn’t really part of the objective. I figured that I would worry about that problem after I had had obtained enough Horemans.

I only keep a very limited number of pigeons (approximately 60), so as the number of Horemans increased, the number of Hofken decreased until I was basically left with five pairs inbred Hofkens from the Topman line.

I began crossing these inbred Hofkens, a Verbart 46 hen, and a HVR hen to the Horemans to produce hybrids. In truth, I was looking at both the Verbart 46 hen and the HVR hen more for their backcrossing potential. This was because the Verbart 46 hen was already a quarter Horemans, and the HVR hen, although quite old, was purchased to bring the T-checking into the family. For her it is a race against time.

The Red Hen - Daughter to the old HVR hen

However, for whatever reason, when mated to the Horemans, both the Verbart 46 hen and the HVR hen produced a much higher level of vigor than did the Horeman/Hofkens cross. At the same time, I also made several Hofkens/Janssen matings, and these also produced a very high level of vigor. Yet, together the Hofkens and the Horemans just didn’t click. Both are excellent families of pigeons, but together, they just didn’t get it done. As the Horemans were primary family at that point, the decision was pretty simple.

Q17 What criteria do you set down for the pigeons you winter with your thoughts on the following seasons racing and breeding?

Typically, when I am racing I try to never let my numbers grow to more than 125 pigeons overall. However, when I am not racing, I generally keep my numbers down to 60 pigeons overall.

Each year, I carefully evaluate the direction of my breeding program. Generally this evaluation takes place immediately after the breeding season has ended, because from a breeding standpoint, their year is then over. However, not every year is like every other. For instance, because I have moved the Hofkens out, I now need to carefully reconsider my whole program. Once the direction of the program has been established, I will review what I have and what I need to purchase in order to reach my new goal. Unfortunately, this process is likely to take several years.

Within my current set of pigeons, there will be those that will help me obtain my goal, and there will be those that no longer fit into the program. The fact that some of these pigeons no longer fit, doesn’t mean they are bad, as I don’t keep bad pigeons. It simply means that they don’t fit any more. I have sold many pigeons from this category that have done very well for other fanciers.

In my breeding loft, there are two groups, those that have bred something and those that might breed something. Pigeons that "have" bred are given precedence over those that "might". The "haves" are evaluated for their ability to produce big winner and high percentages, and their breeding compatibility with others in the loft. It would be nice if every pair produced both big winners and high percentages, but the fact is that most do not. Generally big winners are prominent early on in the life of a family whereas higher breeding percentages are more prominent later on in the life of the family.

In my view breeding compatibility is an extremely important consideration. Compatibility has two facets, how well they mesh genetically, and versatility. The concept of versatility may confuse some readers, so let me explain this facet a different way. If I am comparing 2 cocks against 12 hens, and the first cock matches up with 9 of the 12 hens, and the second cock matches up with 5 of the twelve, then my mind, the first cock is more versatile and therefore more important to the family.

It is my view that highly compatible pigeons will show themselves very early on, and this takes us back to the pigeons that "might" produce. In my breeding loft, by default, these are the first and second year pigeons. I can tell you this because, they fall under a "Two years of trial and you are out," policy.

Without a breeding history, it is less predictable exactly what a yearling pair will produce in their first year of breeding. Because I have little else to go on, most yearlings are paired by phenotype. They will either produce what I expect or they will produce something unexpected. When a pigeon produces the way I expect, then from that point on they are usually much more predictable, and thereby easier to correctly pair. If they produce something unexpected, then I must evaluate the unexpected. While the unexpected is usually bad, it doesn’t always turn out that way. However either way, the offspring had better show up big before the end of the second year.

Sometimes they produce exactly what I expected, but what I expected wasn’t good. Because very very few pigeons are perfect, many have an outright problem or at least a concern. A problem means that the pigeon actually has an identifiable problem. A concern is more of a tendency toward a problem. Sometimes, one parent might have a problem and the other parent might be strong enough in that area to cover the problem. In this case, the offspring either doesn’t have the problem, or the problem has been reduced to a concern. Even when the offspring doesn’t have the problem, one of his parents still does, so that is still the equivalent of a concern in my mind. Generally, I never own or breed a pigeon with anything more than a concern. The fancier needs to be aware that even when a problem becomes a concern, that concern has the potential to improve, remain a concern, or reestablish itself as a problem. Therefore an improving concern a good thing, and a remaining or strengthening concern is a bad thing, and it always results in the offending parent and its offspring being tossed out of the program.

Sometimes the first mating doesn’t work. Maybe the pair throws a problem or a concern that is not readily recognizable in either parent. In this case, I carefully evaluate both pigeons to determine if either of them should be eliminated based on the problem or concern. If they are good enough to continue, I will note the results, split up the pair and re-mate each of them to another pigeon. Since time is really ticking in the second year, I try to mate these pigeon to proven pigeons. Since proven pigeons have obviously produced for me before, I have a pretty good idea of what to expect from them in terms of quality and percentages. If the problem or concern shows up again, the question mark pigeon is eliminated immediately. If the offspring do not meet the proven pigeon’s previous level of productivity, the question mark is eliminated.

Once a pigeon has successfully bred, it will fall in the category of the "Haves". These pigeons are ranked on the ability to help me achieve my goals, their age, their compatibility with other pigeons, what they have produced, and their overall level of quality. Generally, when a pigeon is good enough to crack this ranking, someone else is probably going to lose its place within the ranking.

Some pigeons don’t display a concern or a problem, and neither do their offspring. They may even appear to be great pigeons, but for some reason, just don’t have it. Again, at the end of two years…

I am not interested in stories. It all comes down to goals, being proven, and being unproven and needing to get proven in a hurry.

Q18 Do your stock birds get any liberty or are they strictly prisoners?

While I believe that letting breeders out is beneficial to their health, the loss of even one key pigeon could have a devastating impact on the breeding loft. I have known many fancier that let their breeders out, and, in every case, they have sung the blues when they lost a great one. In my view, it is critical that the fancier have more control over his breeding program than that. The truth is that most pigeon produce through their tenth year regardless of whether they are allowed to fly out or not, so while there may be a minimal health advantages, those advantage can be quickly erased through a single loss.

Q19 Do you think a pigeon has the capabilities of racing both short and long distance races? What distances can a pigeon actually still "RACE" as opposed to homing from any race point?

While there are very few pigeons that can win at any distance, on an individual basis, most pigeons are capable of maintaining pace with the front flock in the shorter races when they are in shape. For instance, as I mentioned above, my Hall of Fame pigeon, Prime Time, was on the drop with eight other pigeons on the 125 mile race, but then she went on to win the 400, 500 and 600 mile races outright. She was clearly a distance pigeon, but there she was on the 125 mile race. However, in cases where the front flock is made up of a number of truly great short distance pigeons, very few distance pigeons are going to be able to hang with them. This would be particularly true in Europe with their specialized competition. Still, here in the United States, when you look at the short distance races, especially in the bigger combines, it is very rare that one pigeon is out front.

As far as the best distance for racing verses homing, I would have to say that in young birds on a fast course, any race is a race up to 400 miles, and on a slow course, any race is a race up to 300 miles. In old birds, I would say that races under 400 to 450 are won by racers and above that distance, homers tend to take over. This is not to discredit homers, as they very clearly have their place in the sport, and in some ways I tend to like them better as they tended to be stronger and more reliable. With fewer and fewer fanciers, sometimes the longer races don't have the competition, but they still must fly against the elements.

Q20 How do you go about bringing in a new bird or family and what do you look for?

This is an interesting question for me at the moment. As I have already stated, I was looking to produce hybrids through the Hofkens/ Horemans cross. By taking these two inbred families and mating them together, the goal was to produce a super hybrid. However, in my articles, I have always referred to using two inbred families as flying blind. Since the members of both families are inbred, they are difficult to race straight, and, therefore, they are difficult to test as individual families. Instead, in this situation, the fancier has to rely on the hybrid product of the two families.

The fact is that once a fancier starts down the path of inbreeding, it is very easy to get caught up in the inbreeding process to the point where eventually everything becomes too inbred. While in itself, inbreeding for a generation or two is probably a good thing, too much inbreeding can be a bad thing, especially when you can’t really basket test the inbred sides of the family.

Therefore, I am starting to change my philosophy, and now that the Hofkens are gone, this is much easier to do. Instead of looking for the super hybrid, I am going to start working with a weaker form of the hybrid.

Going forward, I am going to maintain my inbred Horemans family, and I am going to bring in winners from other families. This way, I will be able to mate winning pigeons directly against the Horemans family. When one of the hybrids does extremely well in the races, I will backcross it into the family, which is something that I couldn’t do under the two family system without mixing the blood of the two families. In fact, this is how Ed Lorenz built the Horemans family in the first place.

Let me give you a quick example of how this works. Ed Lorenz sold his good friend, Dave Hunsicker, several Horemans cocks out of his foundation cock 2234. Dave in turn crossed those cocks into his pigeons, and sent several of the offspring to Ed to fly in the Summer Classic. One of these pigeons, 1207, turned out to be a superstar, winning the Summer Classic average speed by over 20 minutes. Ed then crossed this pigeon to 2234’s son 1192, which happened to be the best racer that Ed ever owned (16 time diploma winner). 1207 and 1192 produced the great breeder 7730, which was then mated back to 1207 again to produce the three brothers that I talked about earlier. Ed then took the second best of the three brothers and mated it to 1207 again, and this mating produced my 54 hen (A.K.A "The Park Rat.") As you can see, in the first generation there were two great winners, and the great winner 1207 is in each of the remaining generations. Therefore while I am now down several generations, the direct mother, grandmother and the great grandmother are all the excellent race hens, 1207.

"The Park Rat" - double inbred daughter to the great hen, "1207"

Q21 Which of the two sexes do you consider is the most important when it comes to breeding? Racing?

It is very easy to go on about this topic for an hour, and all you will accomplish is that you will make your head hurt. In my view, the hen adds stability or consistency, and the cock adds greatness. If you have a great line, then you want to keep that line by using a cock from the line. Therefore, if you want to introduce new blood from a different line, you can do so by bringing in a hen from that line and mating it to the great cock from your line in much the same manner as Ed did with 1207.

Sometimes the fancier winds up obtaining a cock instead of a hen from another line. The way I handle this problem is to mate the cock from outside the family to a hen from my line (preferably an inbred hen), and then take the best hen from the mating and mate it back to a great cock from my line.

Someone recently pointed out to me that some fancier in Europe are loaning their very good hens to fanciers with a champion cock. They then take a daughter from that mating and mate it to an outstanding cock in their own family. This brings the winning genes of the cock from the outside family back into your family and in a more usable format. While this is exactly what I was suggesting in the above paragraph, the advantage here is that the owner doesn’t have to give up the ownership of his champion cock.

Q22 When it comes to breeding do you line-breed or use a first cross or just pair winners to winners?

Racing pigeons is a complicated sport that takes up a great deal of time, so most fanciers are more interested in obtaining first generation winners then they are in building a long-term family. These fancier would rather focus on winning races than breeding. When a breeder gets old or doesn’t produce well enough, they simply buy something else. Given that there is only so much time in the day, there is certainly some logic to this approach.

For most fanciers, first generation crosses are pretty successful, and, this is because, for all practical purposed, this is the weakest form of hybridization, but it is a hybrid none the less. However, most fanciers achieve far less success in the second generation, and often find it easier to go buy new pigeons and start all over again. A few fanciers are able to line breed their way into some level of genetic consistency in about four or five generations, and, through this process, they are the ones that eventually build a family. As genetic consistency increases, some fanciers switch form line breeding to inbreeding, and, when they are successful with this approach, they usually become highly successful fanciers at least until the breeding becomes too close. While there are cases where fanciers have done well inbreeding in the first generation, these situations are extremely rare, especially if the inbreeding continues for several generations thereafter.

Q23 What is the importance of the throat and what do you look for? In regards to the upper palate slit should it be closed or open? I have seen some birds with a standing tongue i.e. does not lay flat. Is this a fault?

Let’s start this off with a quick discussion about the quality of the pigeon vs. its health. A quality pigeon is also a healthy pigeon, but a healthy pigeon is not necessarily a quality pigeon. Therefore, quality is inclusive of health, but health is not necessarily inclusive of quality and this puts quality before health. Yet, when health suffers, it directly detracts from the overall quality of the pigeon.

Much of a quality pigeon has to do with its genetic makeup, but much of that genetic makeup is enhanced by health. For instance, a pigeon can have genetically superior feather, but when that pigeon is unhealthy, the feather will not show those superior genetic qualities.

In a way, the throat is a sign of both quality and health. By definition, a quality pigeon will possess the genetics to have good a throat, and the health to maintain a good throat. However, when a quality pigeon becomes sick, stressed, or worn down, it will start to show signs of that fatigue in the form of reduced body maintenance. The throat is one of many areas where this reduction in maintenance can be seen. Again, by definition, a quality pigeon can endure more without getting sick, and, even when a quality pigeon does get sick, it can better endure the sickness. However, there is a breaking point for every organism, and prolonged sickness will eventually draw the quality right out of the pigeon.

When I grade pigeons, I am often handed what once was a quality pigeon; however, through poor care, it is now just a pigeon. Genetically, it is still the same pigeon, but physically it isn’t the same, and it will never breed the same again either. It is broken. Some will believe that they can fix the pigeon through medication, but the pigeon is sick because its immune system is shot, and medication can’t fix a broken immune system.

As a grader, I don’t have a great deal of time to be looking down every pigeon’s throat. In fact, there are very few grading situations where the lighting is probably good enough to do this anyway. Therefore, while signs of poor health are certainly present in the throat, they are almost always present elsewhere as well, so when I am grading, I don’t pay as much attention to the throat.

At home where I have more time, I do occasionally look at a pigeon’s throat. When I do so, I always look at the general color of the sidewalls of the mouth, especially in the area just behind where the beak comes together in the back. While I would never see it in my loft, many pigeons have a purple sidewall in this area, and these pigeons are shot. Pigeons with wide open clefts that hang down are also shot. Pigeons with clefts that are tightly closed are too fat and out of shape. Pigeons with gray tongues have trouble dealing with the by product of protein, lactic acid, and these pigeons will fatigue far more easily. While there are some pigeons that have a gray pigmentation to the tongue, their tongues are usually darker and shiner than the normal gray tongue. Pigeons with tongues that stick to the bottom of the mouth are too dry, and pigeons with tongues that stick up too much will often have a sting of spit from the tongue to the top of the mouth when the mouth is first open it, and they are too wet. Pigeons with more than a few small yellow spots on the palate of the throat should be discarded. Pigeons with puffiness of the palate or disfiguration of the cleft line in the palate should be discarded. Pigeons with yellow mucous in the bottom corners in the back of the throat should be at least questioned. Pigeons that appear to be in good health, but have their trachea wide open should be discarded. Pigeons with pale white tongues should be questioned.

In the end, when it comes to the throat, the optimum word is pink. Not a white pink or a purple pink, but a rich pink.

Q24 Can you explain your interpretation of balance? Is it the conformation, feel in hand, general look?

Proportional balance is about having all the right tools for the job at hand. However, certain pigeons have subtle differences in the shape of their body that actually allows them to work more easily in flight, and these pigeons are generally much more consistent from week to week. Pigeons that are in balance fit deeper in the hand, and the keel bone tends to fit more smoothly across all of the fingers. In fact, the shape of the keel and how the weight is distributed across the keel bone has a great deal to do with the balance of a pigeon. Many of the older families had much better balance than many families do today. This is in great part because many of the older families were hen based families, and hens usually have better balance than cocks.

Q25 What shape of body do you prefer? Apple, pear, shallow deep?

Personally, I want to have the right tool for the job. Apple bodied pigeons tend to do better at the shorter and middle distances. Longer shallower pigeons tend to do better at the longer distances. If you stay with your family of pigeons for a period of time, you will soon find that they tend to weed down to the right type of pigeon for your course, and regardless of what we tend to think, these are the right pigeons for the course.

As a grader, I have been to several areas where the races are extremely consistent from week to week. Because of this consistency, there are amazing similarities in the physical characteristics amongst pigeons flown on these courses. From pigeon to pigeon, there is still a difference in quality, but from the standpoint of a physical shape, they are amazingly similar. This would imply that pigeons do tend to adapt to the course.

Q26 What are your views on " Acclimatization " Do you think One Loft/Futurity birds bred to race on the site of the loft have an advantage of any kind?

Acclimating to a new environment is highly stressful to the pigeon, and, therefore, how it is handled is extremely important. In fact, the more extreme the climate, the more the pigeons need to be watched. In the first year at a new location, new pigeons shouldn’t be treated the same as the rest. The fact is that when a pigeon is move to a new location, its immune system becomes more vulnerable, and it can get sick much easer. Therefore, to help get them back into cycle, I generally try to mate them after March, and I generally try to limit their breeding to two rounds in that first year. I don’t want them to sit unused, but I also don’t want them to get tired. When pigeons are mated, their immune system tends to naturally strengthen, and by breeding two rounds from them, the pigeon will start the molt correctly, which in turn purifies the blood. If the pigeon goes through all of these steps, it should be ready to go the following season.

Pigeons that do not acclimate after the first molt either are not healthy enough, or they lack the ability to fight off certain environmental elements. For instance, Chlamydia is very common here. While the native pigeons have little trouble with it, about half of all the pigeons that I bring in seem to have a great deal of trouble with it. Therefore, over time, I have learned to watch for any sign of Chlamydia, and I generally eliminate those pigeons that display signs very quickly.

By the way, acclimation is one of the major reasons that I try never to purchase pigeons that are over seven years of age. Assuming that they are seven, and it takes a year for them to fully acclimate, then the pigeon is already eight by the time I get my first real chance to test the pigeon.

As far as one loft races are concerned, when competing with the locals, I think most fanciers are trying to overcome two problems. The first is obviously environmental acclimation and course adaptation. Obviously, pigeons that have lived in the area and have flown the course are going to be much more adapted to that course. This is why many areas started promoting the idea of the best out-of-area pigeon.

Q27 When, and if, you assess or grade a photo i.e. via internet etc and it is a good photo of a bird what do you look for in comparison to being able to grade by handling?

This is a difficult topic to explain, but it has a great deal to do with certain proportional aspects of the pigeon’s makeup and health. If you go to the chiropractor, they will often speak of the body being out of alignment. Well, pigeons also have many alignments as well, and each alignment means something different. The shape and angle of the wing butts or back, the length and width of the body and even the neck and head all have correct alignments and they can all have a great deal to do with the pigeon’s overall ability. Certain aspects of the health of a pigeon also tend to show up in a picture as well. Clearly some do a great deal of touchup to their pictures, but it is hard to touch up the shape of the head, the relationship of the eye to the beak, and the shape of the wing butts, and, at this point, I can generally tell what has been touched up and what hasn’t.

Q28 How does the quality of European birds compare to North American birds?

Many highly intelligent people enroll at Stanford because that is where smart people go to college. However, I am sure that if you took the top students from almost any major University across the United States or Canada, they would probably be just as smart, but there might not be quite as many of them at any one location. It is kind of the same thing when comparing North American to European pigeon racing. Clearly, there are more pigeons in Europe, and, therefore, it stands to reason that there would be more good pigeons in Europe. However, at the same time, the very best here are easily as good as the very best there.

Many of the great European lofts happen to live in the southwest corner of their province, which happens to be the short end. Because they post great records, we tend to import more of their pigeons, so, in affect, we are buying their airline. At the same time, pigeon adapt to courses, not courses to pigeons, so even when we are fortunate enough to import some good pigeons, they are not necessarily the best for our course.

Years ago, I think there was a much bigger difference in quality between their top lofts and ours, but so many of the great pigeons have been sold out of Holland and Belgium, that I think that gap has closed significantly.

Q29 Do you practice or study eyesign?

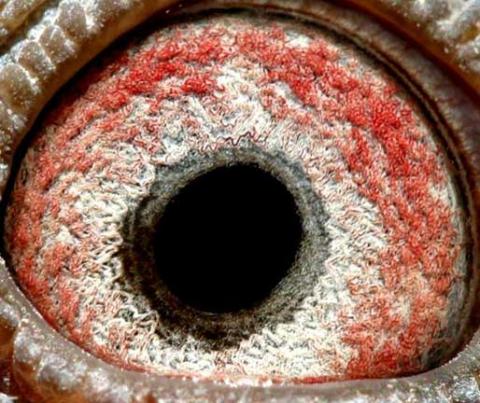

Daughter of the Golden Hen - "6034"

Why is it that the last question is always the hardest? Clearly, I do not follow or preach eyesign in the traditional sense of the word. After listening to one of my seminars in Europe, my host started introducing me as the leading expert, and maybe the only expert in the field of eye mechanics. After hearing the phrase "eye mechanics", I kind of adopted it because it probably best describes my approach to the eye.

If you can still remember back to the beginning of this interview, you might remember that I mentioned my involvement in the study of pigeon eyes at the University of Arizona. Well, eye mechanics was certainly directly and indirectly related to everything that went on in that study. The difference between eyesign and eye mechanics is quite simple. Eyesign is about identifying common structural patterns within the eye. Eye mechanics, involves an explanation for these patterns, and what the patterns are designed to do.

Just prior to my visit to Aalst, Belgium, the chat rooms on the internet were abuzz with discussion about my visit. The gist of these discussions was that no one had ever come to Europe to give a seminar, and, from what they knew about me, I was just another eyesign nut from the United States. To make matters worse, in the weeks leading up to my visit, I had graded many eyes and pigeons from pictures that fanciers had sent into the Winning Magazine site. Many were saying, "How was this possible." There was such a clamor in the chat rooms that many fanciers were threatening not to come to the seminar that was scheduled for 7:00 p.m. that night.

Unfortunately, I was scheduled to grade over 500 pigeons between 11:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. that same day, so by the time I got finished, I was already kind of tired and in no mood for a fight with the locals. However, while I was grading, in the back of my mind, I kept thinking that no one would attend the seminar anyway, so it wasn’t going to be a problem.

Fanciers signing up for the grading session in Aalst, Belgium

When I was finished grading, my host drove me at warp speed to a large pub in the center of town, and, when I walked in, there where approximately 300 highly skeptical faces waiting for me. You might say that by the time I got there, they had worked themselves into a fine frenzy.

Sold out seminar in Aalst Belgium –This picture was taken well into the seminar when they were in a good mood.

Now, I never wear an overcoat when I am grading pigeons, but because I couldn’t bring along enough clothes to be changing after every grading session, someone had given me a bright white overcoat. I didn’t have the heart to tell this person that big bright white moving objects tend to scare pigeons, so I ended up wearing it the entire trip. Therefore, when I entered the pub not only were these fanciers all worked up about what I might say, but now they now had my white overcoat to chew on as well, and, believe me, they were chewing! They were conferring amongst themselves, while at the same time never taking their eyes off of me like I was wearing a straightjacket or something. Although I don’t speak Flemish, I could pretty well figure out that my white overcoat wasn’t winning any points.

Grading the pigeons of the excellent fancier Chris Cleirbout

(Notice the famous white coat)

I proceeded to quickly strip that ridiculous white overcoat from my body, and then I started off by saying, "Now how many of you believe in eyesign?" Given that they were all there to watch me choke on the subject, not one person raised their hand. I followed this up with, "Good because neither do I." That left them confused and waiting for an explanation.

I finished up with my basic speech around midnight, and then I asked them if they wanted to hear a little about how I was able to grade pigeons from a picture. Given the hour, I was sort of surprised when they all wanted to go on. Amazingly, it went on until 1:00 a.m., and not one person left early.

The highly respected veterinarian Geert de Schepper and Assistant Editor for Winning Magazine, Eddy Noel, just after the 1:00 a.m. conclusion of the seminar in Aalst, Belgium.

Today, a year later, and I still get about 10 emails a week from fanciers who attended at least one of my seminars, and they still talk about the wonders of eye mechanics.

In closing, I would again like to thank Ali for the opportunity to do this interview. I apologize if I went on too long in some areas. As I am not accustomed to doing this type of interview, I will say that it was difficult to know exactly how in-depth to go with some of my answers.

I thank you for your time.

Book

Selection and Breeding

General Management

Feeding

Medication

Andy Loudon

Mid Island Racing Pigeon Association

Qualicum Beach , BC V9K 2L7

Phone: 250-268-8571

|